A desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) foraging in a patch of the native annual forb desert plantain Plantago ovata in southern Nevada in 2004. Photo by R.J. Abella.

Knowlege is Power: Protecting the Desert Tortoise

NEXUS project uses ecological knowledge to enhance the habitat quality for threatened desert wildlife

By Jane Palmer

May, 2018

The desert tortoise might be Nevada’s state reptile but rapid changes in fragile desert ecosystems could threaten its very existence. In the last 150 years, non-native animal and plant species, and new towns, roadways and railways have infiltrated the Mojave and western Sonoran Deserts, the stomping ground of the Desert Tortoise. It’s an evolution that has led to both habitat loss and habitat degradation for this iconic species.

More recently, the construction and deployment of solar power facilities has further fragmented the tortoise’s home and altered the topsoil and land cover disturbing the available food supply. As a first step in mitigating these impacts, Scott Abella, an assistant professor in the School of Life Sciences, University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) and his team have previously investigated how to reintroduce native plants into the desert environment.

University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) undergraduate students who planted 800 native trees at Lake Mead. Photo by Josh Hawkins, UNLV Photo Services

Now the NEXUS researchers are taking their research one step further: Using the knowledge they have gleaned from their previous studies to determine how desert tortoises use these enhanced environments.

“Our project bridges a gap between the basic ecology of the desert tortoise and the development of practical conservation strategies for enhancing habitat quality in disturbed areas such as near renewable energy facilities,” Abella says.

Focusing on Forage

In 1990, due to the reduced numbers of the desert tortoise, the population in the Mojave and western Sonoran Desert was federally listed as threatened under the US Endangered Species Act. But since that date, tortoise numbers have not recovered; rather they have continued to drop. Between 2004 and 2014 the estimated decline was 32% for desert tortoises in designated recovery areas.

“This decline is considered serious because reproduction is also poor, raising questions as to whether desert tortoise populations can sustain themselves or continue to decline,” Abella says.

In response to the disturbing trend, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service prepared a Revised Recovery Plan for the desert tortoise in 2011. In this plan the scientists emphasized habitat conservation, enhancement, and restoration as priority recovery actions.

“Conserving habitat for tortoises is important because they need safe ‘living spaces’ that provide them with their basic needs, similar to human needs for food, water and shelter,” Abella says.

One of the areas with the greatest potential for enhancing quality of desert tortoise habitats is improving the quality and quantity of forage, Abella says. Currently, non-native annual plants mostly dominate the tortoises’ habitat.

“Non-native grasses such as red brome that have pervasively taken over the tortoises’ habitat are not good for tortoises,” Abella says. “These non-native plants provide poor nutrition and may have replaced ‘multi-vitamin’ native wildflowers.”

Consequently in 2012 Abella began to investigate ways of improving forage quality on Bureau of Land Management (BLM)-Nevada lands in Clark County, Nevada, just north of the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility. The study site is a Large-Scale Translocation Site where scientists relocate tortoises rescued from other areas.

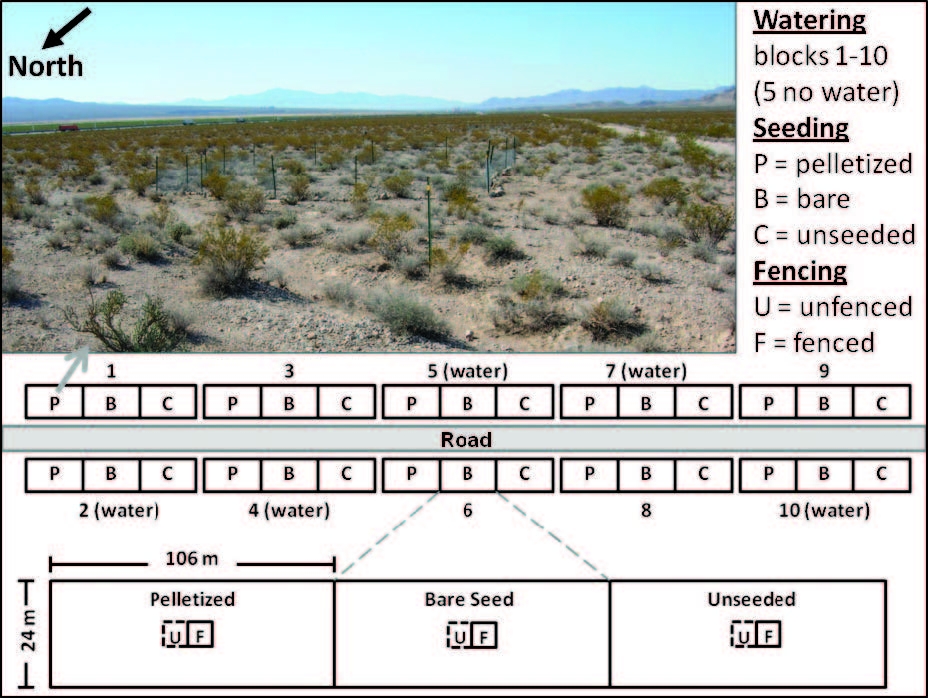

In collaboration with the BLM, Abella and his UNLV team began to enhance the habitats of 60, hundred-square-meter plots by a variety of techniques such as fencing off the areas to keep large herbivores out. To investigate techniques to improve the forage quality in 2012 Abella began to test seeding with the native desert plantain, desert globemallow, and two shrub species—cheesebush and winterfat—that provide cover in the desert tortoise habitat of southern Nevada.

Experimental layout for testing forage augmentation treatments for the desert tortoise Gopherus agassizii in southern Nevada during 2013 and 2014. Photo by S.R. Abella, September 2014.

By the end of the first year, Abella found that pelletized seeding quadrupled the density of desert plantain. Fencing off these seeds then tripled the density of these plants. “This research showed that augmenting native annual forage plants favored by desert tortoises is feasible,” Abella says. “Desert plantain is a native wildflower nutritionally useful to desert tortoises.”

The study was published in the Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management in 2015, and The Desert Tortoise Council named it the Research Project of the Year, attesting to the novelty of the approach in improving the desert tortoise habitat.

The true test of the effectiveness of the research lies in whether it ultimately helps the tortoises, however, Abella says. “The next step of this research would involve evaluating how desert tortoises respond to improvements in forage quality,” he says.

One of the areas with the greatest potential for enhancing quality of desert tortoise habitats is improving the quality and quantity of forage, Abella says. Currently, nonnative annual plants mostly dominate the tortoises’ habitat.

“Non-native grasses such as red brome that have pervasively taken over the tortoises’ habitat are not good for tortoises,” Abella says. “These non-native plants provide poor nutrition and may have replaced ‘multi-vitamin’ native wildflowers.”

Consequently in 2012 Abella began to investigate ways of improving forage quality on Bureau of Land Management (BLM)-Nevada lands in Clark County, Nevada, just north of the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility. The study site is a Large-Scale Translocation Site where scientists relocate tortoises rescued from other areas.

In collaboration with the BLM, Abella and his UNLV team began to enhance the habitats of 60, hundred-square-meter plots by a variety of techniques such as fencing off the areas to keep large herbivores out. To investigate techniques to improve the forage quality in 2012 Abella began to test seeding with the native desert plantain, desert globemallow, and two shrub species—cheesebush and winterfat—that provide cover in the desert tortoise habitat of southern Nevada.

Putting Knowledge to Use

While Abella’s earlier research proved hopeful, scientists have already established that the variation in the availability of such plants over time is key to desert tortoise health, making long-term results important. So, with support from the NEXUS project, Abella and his team began to measure the forage conditions for tortoises again in the translocation site plots through Spring 2018. In addition the researchers are measuring how desert tortoises use these enhanced habitats.

“This work can help establish for how long restorative actions can augment forage for tortoises,” Abella says. For example, good forage plants might be persistent if their seeds have become stored in the soil enabling them to germinate in future years of good rainfall. “The seeds would not have been there if not for the restoration actions,” Abella says.

The scientists began counting signs of tortoises in the restored habitats and comparing any signs of usage to those in the unrestored areas. These counts and the monitoring of the forage quality are continuing through the spring of 2018.

Abella hopes that the research will help advance scientist’s understanding of how desert tortoises respond to habitat enhancement activities occurring near solar facilities. But the knowledge gleaned from the study could translate to other areas disturbed by construction or road building.

“By linking ecological knowledge of desert tortoise foraging ecology with habitat enhancement actions, this project can help inform conservation planning to ameliorate degradation of desert tortoise habitats,” Abella says.

Pelletized seed immediately after seeding in January 2013 in desert tortoise Gopherus agassizii habitat in southern Nevada. Photo by E.C. Engel.

NEXUS Funding Plants the Seeds of Environmental Awareness

Tiffany Pereira, UNLV graduate student and artist, inspired by her ecosystem research to paint the native endangered plant, the Las Vegas bearpoppy. On display now at the Nevada State Museum.

When Scott Abella presented at the recent NEXUS annual meeting he spoke proudly of the many students that had become involved in restoration ecology or conservation ecology directly, and indirectly, thanks to project funding. Abella showed slides of the large group of undergraduate students who planted 800 native trees to restore the shifting shoreline habitat at Lake Mead—students that even after a 12-hour day refused to leave until all the trees had been planted. He also spoke of students such as Vivian Sam, who had originally been a summer intern funded by the Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-serving Institutions grant. As a graduate student Sam is currently restoring native plant species on her tribe’s ancestral native lands along the Colorado River.

Vivian Sam, UNLV graduate student. Photo by Josh Hawkins, UNLV Photo Services.

Abella has also been able to offer classes and field trips for undergraduate students on topics such as arid soils, restoration ecology and forest ecology—all of which provide valuable data which will inform the scientists and conservationists of the future in how to mitigate the impacts of energy development on desert ecosystems. Abella encourages students to not only study the ecosystem but to communicate what they discover to a broader audience. One of Abella’s graduate students, Tiffany Pereira, is conducting research to evaluate the long-term change in soil seed banks, fertile islands, and plant communities of conservation-priority gypsum rare plant habitat of the eastern Mojave Desert. Pereria also paints the desert environment and a permanent exhibition of her scientific painting can be viewed in the Nevada State Museum, which is visited by seven million people a year.

“By funding Scott Abella as a new faculty hire, the NEXUS program has impacted the futures of many students and, in turn, the conservation of desert ecosystems,” says Dr. Gayle Dana, NEXUS Project Director.

_______________________________________

NEXUS Notes is a monthly publication of the Solar Nexus Project, which is a five-year research project funded by the National Science Foundation’s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research “EPSCoR” (Cooperative Agreement #IIA-1301726) focusing on the nexus of (or linkage between) solar energy generation and Nevada’s limited water resources and fragile environment.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

_______________________________________

If you would like to know more about the NEXUS project,

please contact, Dr. Gayle Dana

Gayle.Dana@dri.edu

530-414-3170

_______________________________________