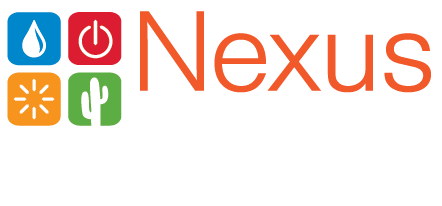

Martin Next Generation Solar Energy Site 2012 (post-development) –Google Earth Photo

A Bird’s Eye View of Solar Facility Impacts

NEXUS scientists use remote sensing to determine how solar energy installations influence surrounding ecosystems

By Jane Palmer

June 1, 2016

Large-scale solar power plants offer a sustainable supply of energy with little greenhouse gas emissions, but scientists still don’t have a complete picture of how these installations impact the surrounding environment.

“We don’t have enough resources to do a detailed ground study,” says NEXUS scientist Haroon Stephen, an assistant professor in the department of civil and environmental engineering and construction at the University of Nevada Las Vegas (UNLV), “and we can’t always connect to the history, what the environment was like before the solar installation was there.”

To address these gaps in the data, Stephen is using remote sensing data to get a bird’s eye view of the land surface prior to any building, during construction and in the years after installation. Using data from the Landsat satellite, which has been providing land surface information for more than three decades, Stephen and his team have been able to get a unique perspective on the impacts of solar energy installations.

“Having the historical perspective of the site is something that can give you additional information which you wouldn’t get if you were just going and seeing it after the building,” Stephen says.

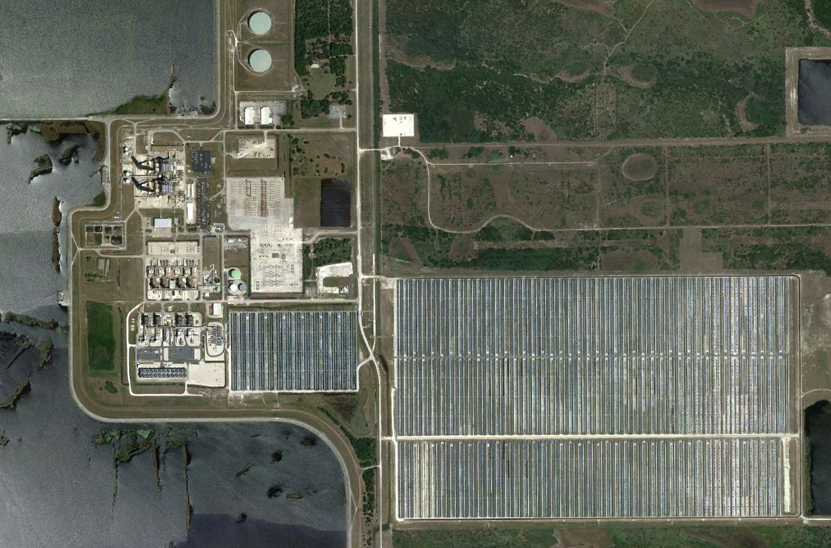

Nevada Solar One Site 2004 (pre-development) and 2012 (post-development)

–Google Earth Photos

Plants Prove Key

Using images from the Landsat satellites and the National AgricultureImagery Program, Stephen and his NEXUS graduate student,Mohammad Masih Edalat, investigated the land surface changes at three sites: the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System in California, the Nellis Solar Power Plant in Clark County, Nevada and the Nevada Solar One site near Boulder City, Nevada.

Inspecting the satellite data, the team found that the installation changed the albedo-the ability of the land to reflect light-of the land surface within the sites both during and after construction.

“If there was pre-existing vegetation and that vegetation was removed and bare soil was exposed, that will show up as a change in the albedo of the surface,” Stephen says.

The scientists observed that the bladed land reflected more light, that can contribute to lower temperatures within the sites. The panels themselves also reflected light and created shadows further cooling the land.

In addition to this impact, the scientists noticed that concrete buildings and roads also increased the reflectivity of the land surface. But outside of the installation site, the findings proved surprising.

“We thought there’d be a halo effect of the facility,” Stephen says. “In the immediate vicinity we would see some impact on the albedo and as you go farther away that impact reduces.”

Instead the researchers found almost no impact on the reflectivity or temperature immediately outside of the facilities. “What we are finding is that the facility itself has it’s primary impact when it is built but we are not seeing any secondary effect other than the road network that is built to get there,” Stephen says. “We’re not seeing any secondary effects on the neighboring vegetation or neighboring soil.”

For arid regions, the news is good, but Stephen emphasizes that the impacts might prove more significant when more plants existed prior to installation. When Stephen’s undergraduate student James Reynolds looked at the impacts of solar installation in less arid regions he found greater changes in the surrounding environment. The findings imply that it is the removal of vegetation, rather than changes in reflectivity, which truly impact the ecosystem.

“So one of the take home messages is that when any of these facilities is being constructed, care should be given in recognizing how is the vegetation impacted because that will have impact on pretty much every ecosystem-related aspect in that area,” Stephen says.

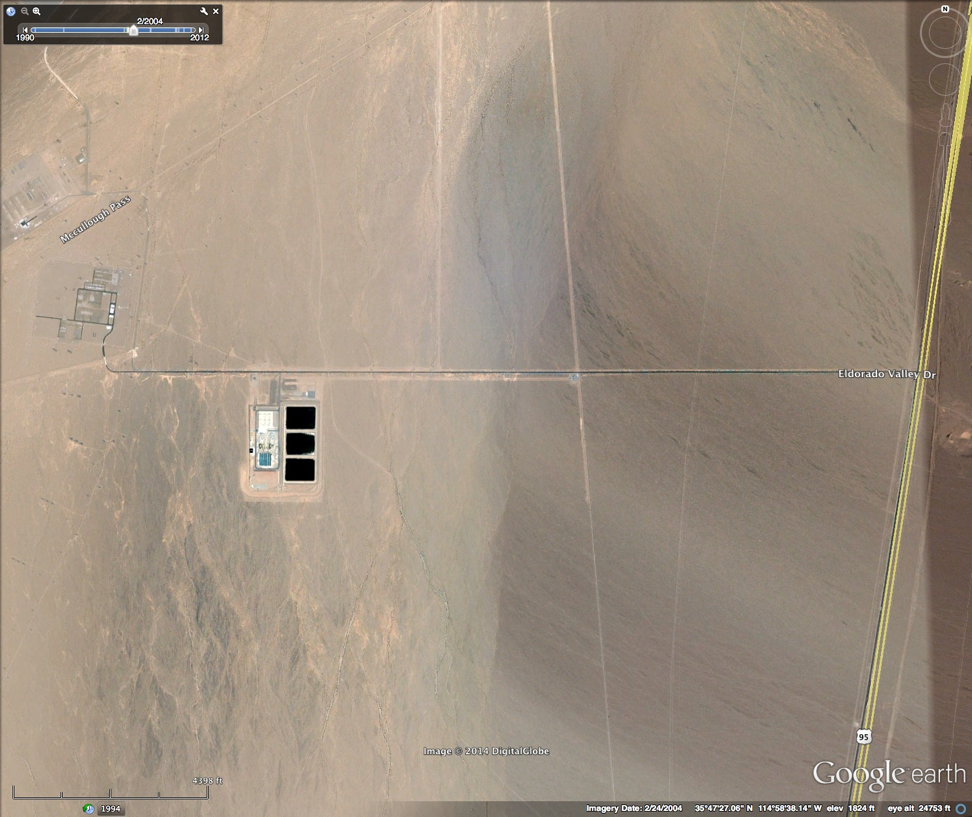

Nellis Solar Power Plant site in 2006 (pre-development) and 2010 (post-development)

–Google Earth Photos

Toward a Holistic Perspective

The scientists have also begun to investigate how solar installations might change the surface hydrology within and near the sites. At the Nellis Solar Power Plant in Nevada, the team has attempted to use remote sensing to see how construction might have caused elevation changes in the land surface, “because water flow is very sensitive to how elevation changes,” Stephen says.

The researchers are recreating a before scenario of the site’s elevation, modeling the consequent hydrology, and comparing their findings with the current hydrological model. Their preliminary analysis reveals that the installation has had an impact. “Water stops behaving the way it was behaving when it was natural surface,” Stephen says.

Removing vegetation and grading the land increases the speed of water flow, but the solar installations can also serve as obstacles that reduce the flow, Stephen says. The scientists are now conducting further analysis to understand all the factors that impact the surface hydrology.

In the future, the team also hopes to compare and validate their findings with on-the-ground measurements of the surface hydrology. NEXUS scientist Dale Devitt has already installed ground instrumentation to measure surface characteristics and hydrology.

“We will end up feeding into the research done by other researchers on the ground,” Stephen says. “So we will provide a historical perspective of these things and also a large scale perspective and it will give them a bird’s eye view of what is going on.”

Stephen believes that such collaborations will contribute to a successful understanding of the impacts of solar energy sites. “I have a very narrow area where I work, and I probably would never have been able to do this on my own,” Stephen says. “But it makes me very excited to see the outcomes of working with all these researchers to achieve a unified goal.”

Devitt’s Environmental Monitoring Site

Brian Bird and Scotty Strachan

–Scotty Strachan Photo

NEXUS Project’s Strengths Lie in Interdisciplinary Collaborations

The NEXUS project is, by its very nature, interdisciplinary. To investigate the nexus between solar energy, water and the environment requires teams of physical, environmental and computer scientists, engineers and hydrologists. But having multiple disciplines working on each issue is simply not enough. For truly effective results the researchers need to enter into collaborative investigations and share their findings.

A key goal of the NEXUS project is to foster such interdisciplinary collaborations. The annual meeting, monthly presentations and faculty retreats all encourage researchers to share ideas and research with one another and enter into interdisciplinary projects.

“Our NEXUS project is providing the mechanism to bring the faculty together to collaborate and create something big and impactful that they couldn’t do on their own,” says Dr. Gayle Dana, Nevada’s Project Director for the National Science Foundation EPSCoR Program.

Already, NEXUS scientists researching solar forecasting are collaborating with engineers to determine how best to integrate solar energy into the grid. This project is one of the many examples of how NEXUS is forging the path to maximizing solar energy’s efficiency while minimizing its impact on the environment.

“The Nevada System of Higher Education has an incredible pool of scientific talent,” Dana says. “At NEXUS, we are ‘mixing and matching’ these scientists from different disciplines to create a truly transformative project, that is more than the sum of its parts.

June 2016